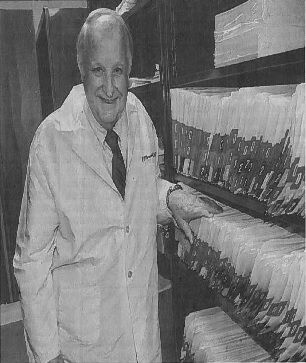

Dr. Don Overstreet, Alpha Phi/Alabama 1952, saw a growing need for family medicine in the rural areas of Alabama and created a hands-on program specifically designed to teach country doctors.

This article was posted with permission from Beth Gribble, Metro Editor, Montgomery Advertiser.

Good country doctors aren’t so hard to find

By Alvin Benn/Montgomery Advertiser

He’s ailing and has trouble getting about, but Dr. Don Overstreet’s memories remain vivid, especially one involving a program that produced country doctors.

It’s called “family medicine” and, while he might not be known to those who benefit the most, his efforts have made him a legend in and out of the healing profession.

At the age of 86, he’s retired and spending his twilight years resting at home in Selma, AL, where he listens to books on tape since macular degeneration has dimmed his vision.

He’s also suffered from osteoarthritis much of his life and relies on titanium hips and knees to maneuver with a walker, but don’t expect to hear him complain.

Those who appreciate his contributions to family medicine have been lining up to praise a man who practiced what he preached as a teacher inside and outside the classroom.

He didn’t just stand in front of the class to explain the nuances of practicing in rural areas, he took his students with him to show them how it’s done.

They watched his bedside manner, his quick response to medical problems big and small and, most of all, his daily successes.

“What he put into place years ago has had longevity, and I’m happy to say it’s still going strong today,” said Dr. Boyd Bailey, a former student who has carried on Overstreet’s UAB Family Medicine program for the past 16 years.

Not all family medicine programs have worked in Alabama, and credit for the successful one based in Selma is, as it should be, directed at Overstreet, who was born at home during a storm in rural Wilcox County and learned early about the importance of country doctors.

It happened one day when an older brother became seriously ill. His family’s doctor not only kept his brother stable, he also drove him to a hospital in Selma for life-saving treatment.

One of Overstreet’s biggest fans commended him recently for committing himself “to the health and well-being of patients too numerous to count.”

Larry Dixon, executive director of the state Board of Medical Examiners, said in a letter to Overstreet: “You have distinguished yourself as both an educator and a public servant for the advancement of medicine and the medical profession.”

Family medicine wasn’t the specialty it is today. Many pre-med students were more interested in high profile, high-paying jobs in large cities.

Overstreet’s commitment to rural health care led him to a career that lasted a year short of six decades. He would have loved being able to practice 60 years, but physical ailments made him more of a patient than a practitioner.

He’s always been a country doctor, beginning in Thomasville, AL where he stitched up bad cuts, repaired broken bones and delivered hundreds of babies, including triplets.

He could see during those years that more physicians were needed to provide healthcare in rural regions where there were few hospitals and even fewer doctors.

The result was a medical program based on families, one that focused on teaching new doctors how to succeed in the country where their presence was needed as much as in big cities.

“He was able to recruit students for his residency program with virtually no funding at first,” said Dallas County Probate Judge Kim Ballard. “Dr. Overstreet was almost a genius in the way he brought them to Selma to learn about family medicine.”

Overstreet did it, in part, by offering prospective students offering prospective students a chance to enlist “in a grand adventure” that would offer them something special in the medical field.

“When he was a country doctor, he never asked patients about their ability to pay,” said Bailey, who inherited the UAB program from his medical mentor. “He’d tell us that if you take care of people the money will take care of itself.”

Bailey said Overstreet imparted to his students his vision for helping the medically underserved in rural Alabama because “he genuinely loves serving people.”

During George Wallace’s early terms as governor, he stressed the importance of rural healthcare and did what he could to find funds for family-based medical programs.

Overstreet provided the drive that Wallace had in mind to lead such a program and when he began, his classes usually consisted of only four students. He wanted up close and personal contact with those who could carry out his rural healthcare vision.

By the time he retired, Overstreet had trained more than 70 men and women to become country doctors. Many are still at it out in “the boondocks.”

Bailey remembers his early days as a rookie rural health doctor when he’d have difficulty with a patient or a case and would ask himself “what would Dr. Overstreet do now?”

“It was his gentle leadership that impressed me most of all,” Bailey said. “I wasn’t the only student who felt like we were one of his sons.”

As he moved into his early 80s, Overstreet operated a medical clinic in the little Dallas County community of Valley Grande. One reason was the need for money to pay for his ailing wife, who had Alzheimer’s disease. She died last year.

He stays in touch with his three daughters and beams over his seven grandchildren when he’s not listening to taped books such as the one about Albert Schweitzer – a Nobel Prize-winning doctor who spent much of his time helping the poor in rural areas.

Those who know Dr. Don Overstreet can see the similarities.